where

Before describing the metrics we use to quantitatively characterize the fractal properties of heart rate and gait dynamics, we first review the meaning of the term fractal. The concept of a fractal is most often associated with geometrical objects satisfying two criteria: self-similarity and fractional dimensionality. Self-similarity means that an object is composed of sub-units and sub-sub-units on multiple levels that (statistically) resemble the structure of the whole object [7]. Mathematically, this property should hold on all scales. However, in the real world, there are necessarily lower and upper bounds over which such self-similar behavior applies. The second criterion for a fractal object is that it have a fractional dimension. This requirement distinguishes fractals from Euclidean objects, which have integer dimensions. As a simple example, a solid cube is self-similar since it can be divided into sub-units of 8 smaller solid cubes that resemble the large cube, and so on. However, the cube (despite its self-similarity) is not a fractal because it has an (=3) dimension. (Click here for a hands-on experiment about fractal curves.)

The concept of a fractal structure, which lacks a characteristic length scale, can be extended to the analysis of complex temporal processes. However, a challenge in detecting and quantifying self-similar scaling in complex time series is the following: Although time series are usually plotted on a 2-dimensional surface, a time series actually involves two different physical variables. For example, in Figure 1, the horizontal axis represents ``time,'' while the vertical axis represents the value of the variable that changes over time (in this case, heart rate). These two axes have independent physical units, minutes and beats/minute, respectively. (Even in cases where the two axes of a time series have the same units, their intrinsic physical meaning is still different.) This situation is different from that of geometrical curves (such as coastlines and mountain ranges) embedded in a 2-dimensional plane, where both axes represent the same physical variable. To determine if a 2-dimensional curve is self-similar, we can do the following test: (i) take a subset of the object and rescale it to the same size of the original object, using the same magnification factor for both its width and height; and then (ii) compare the statistical properties of the rescaled object with the original object. In contrast, to properly compare a subset of a time series with the original data set, we need two magnification factors (along the horizontal and vertical axes), since these two axes represent different physical variables.

To put the above discussion into mathematical terms: A time-dependent

process (or time series) is self-similar if

![]()

where ![]() means that the statistical

properties of both sides of the equation are identical. In other

words, a self-similar process, y(t), with a parameter

means that the statistical

properties of both sides of the equation are identical. In other

words, a self-similar process, y(t), with a parameter ![]() has

the identical probability distribution as a properly rescaled process,

has

the identical probability distribution as a properly rescaled process,

![]() , i.e., a time series which has been rescaled on

the x-axis by a factor a (

, i.e., a time series which has been rescaled on

the x-axis by a factor a (![]() ) and on the y-axis by a factor

of

) and on the y-axis by a factor

of ![]() (

(![]() ). The exponent

). The exponent ![]() is

called the self-similarity parameter.

is

called the self-similarity parameter.

In practice, however, it is impossible to determine whether two processes are statistically identical, because this strict criterion requires their having identical distribution functions (including not just the mean and variance, but all higher moments as well). Therefore, one usually approximates this equality with a weaker criterion by examining only the means and variances (first and second moments) of the distribution functions for both sides of Eq. 1.

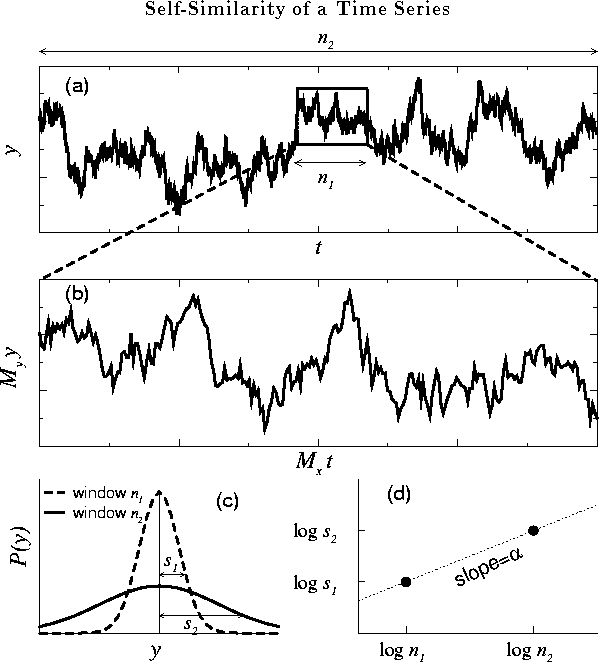

Figure: Illustration of the concept of self-similarity for a

simulated random walk. (a) Two observation windows, with time scales

![]() and

and ![]() , are shown for a self-similar time series y(t). (b)

Magnification of the smaller window with time scale

, are shown for a self-similar time series y(t). (b)

Magnification of the smaller window with time scale ![]() . Note that

the fluctuations in (a) and (b) look similar provided that two

different magnification factors,

. Note that

the fluctuations in (a) and (b) look similar provided that two

different magnification factors, ![]() and

and ![]() , are applied on the

horizontal and vertical scales, respectively. (c) The probability

distribution, P(y), of the variable y for the two windows in (a),

where

, are applied on the

horizontal and vertical scales, respectively. (c) The probability

distribution, P(y), of the variable y for the two windows in (a),

where ![]() and

and ![]() indicate the standard deviations for these two

distribution functions. (d) Log-log plot of the characteristic scales

of fluctuations, s, versus the window sizes, n.

indicate the standard deviations for these two

distribution functions. (d) Log-log plot of the characteristic scales

of fluctuations, s, versus the window sizes, n.

Figure 2a shows an example of a self-similar time series. We note

that with the appropriate choice of scaling factors on the x- and y-axis,

the rescaled time series (Fig. 2b) resembles the original time

series (Fig. 2a). The self-similarity parameter ![]() defined

in Eq. 1 can be calculated by a simple relation

defined

in Eq. 1 can be calculated by a simple relation

![]()

where ![]() and

and ![]() are the appropriate magnification factors along

the horizontal and vertical direction, respectively.

are the appropriate magnification factors along

the horizontal and vertical direction, respectively.

In practice, we usually do not know the value of the ![]() exponent

in advance. Instead, we face the challenge of extracting this scaling

exponent (if one does exist) from a given time series. To this end it

is necessary to study the time series on observation windows with

different sizes and adopt the weak criterion of self-similarity defined

above to calculate the exponent

exponent

in advance. Instead, we face the challenge of extracting this scaling

exponent (if one does exist) from a given time series. To this end it

is necessary to study the time series on observation windows with

different sizes and adopt the weak criterion of self-similarity defined

above to calculate the exponent ![]() . The basic idea is

illustrated in Fig. 2. Two observation windows

(Fig. 2a), window 1 with horizontal size

. The basic idea is

illustrated in Fig. 2. Two observation windows

(Fig. 2a), window 1 with horizontal size ![]() and

window 2 with horizontal size

and

window 2 with horizontal size ![]() , were arbitrarily selected

to demonstrate the procedure. The goal is to find the correct

magnification factors such that we can rescale window 1 to resemble

window 2. It is straightforward to determine the magnification factor

along the horizontal direction,

, were arbitrarily selected

to demonstrate the procedure. The goal is to find the correct

magnification factors such that we can rescale window 1 to resemble

window 2. It is straightforward to determine the magnification factor

along the horizontal direction, ![]() . But for the

magnification factor along the vertical direction,

. But for the

magnification factor along the vertical direction, ![]() , we need to

determine the vertical characteristic scales of windows 1 and 2. One

way to do this is by examining the probability distributions

(histograms) of the variable y for these two observation windows

(Fig. 2c). A reasonable estimate of the characteristic scales

for the vertical heights, i.e., the typical fluctuations of y, can

be defined by using the standard deviations of these two histograms,

denoted as

, we need to

determine the vertical characteristic scales of windows 1 and 2. One

way to do this is by examining the probability distributions

(histograms) of the variable y for these two observation windows

(Fig. 2c). A reasonable estimate of the characteristic scales

for the vertical heights, i.e., the typical fluctuations of y, can

be defined by using the standard deviations of these two histograms,

denoted as ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively. Thus, we have

, respectively. Thus, we have

![]() . Substituting

. Substituting ![]() and

and ![]() into Eq. 2, we

obtain

into Eq. 2, we

obtain

![]()

This relation is simply the slope of the line that joins these two

points, (![]() ,

, ![]() ) and (

) and (![]() ,

, ![]() ), on a log-log plot

(Fig. 2d).

), on a log-log plot

(Fig. 2d).

In analyzing ``real-world'' time series, we perform the above

calculations using the following procedures: (1) For any given size of

observation window, the time series is divided into subsets of

independent windows of the same size. To obtain a more reliable

estimation of the characteristic fluctuation at this window size, we

average over all individual values of s obtained from these subsets.

(2) We then repeat these calculations, not just for two window sizes

(as illustrated above), but for many different window sizes. The

exponent ![]() is estimated by fitting a line on the log-log plot

of s versus n across the relevant range of scales.

is estimated by fitting a line on the log-log plot

of s versus n across the relevant range of scales.